Autumn / Winter 2021

King’s Impact: War Studies at 60

The Department of War Studies at King’s College London was established 60 years ago. In honour of this, we examine...

Inside King’s

Read time: 7 mins

We are living in a period of intense global, social, technological and economic challenges. This has happened before, and we will undoubtedly face it again. At King’s, we believe that our education, research and expertise can help promote understanding and positive change to these real-world problems. By delivering world-leading and outward-looking research focused on meeting societal need, King’s will make the world a better place.

The need for this has been brought into focus with the outbreak of the Ukraine war earlier this year. Here we share how during this time of upheaval, King’s is using our position to increase awareness, promote understanding and convene the major players to unpick the causes and potential outcomes of this war.

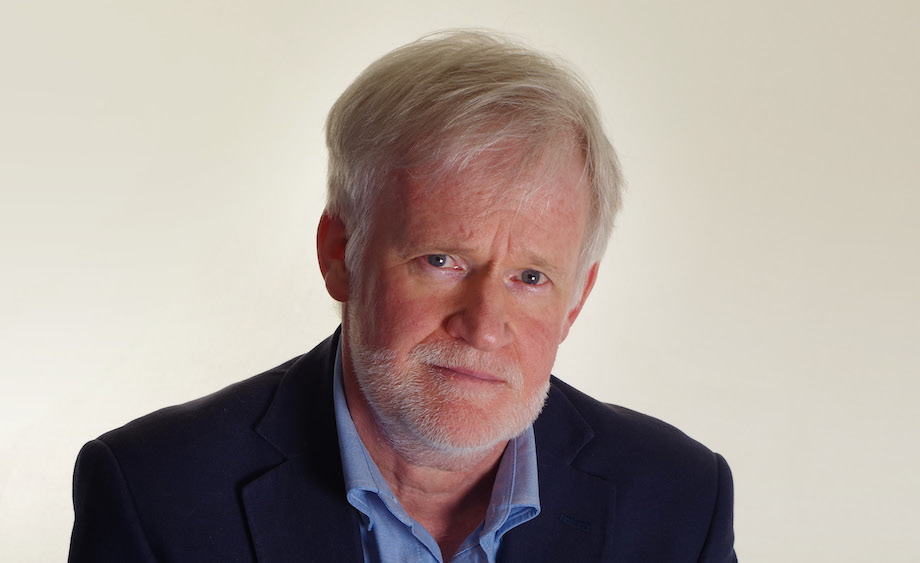

The Faculty of Social Science & Public Policy (SSPP) has world-leading expertise in security studies and deep relationships with government, business, civil society and international organisations. Dr Rod Thornton, a Senior Lecturer in the Defence Studies Department, relays his analysis on the origins of the war.

Dr Rod Thornton

The fact that we now have a major war between two European states is unsettling. It is a conflict that was not foreseen because there seemed to be no logic to it from any perspective outside the walls of the Kremlin. But, looking back, it is possible to discern some rationales for why it happened.

First, it came about in part because it was the ultimate dramatic reaction by Russia to the general pressure it has felt from the West since the end of the Cold War. The spread of liberal democracy across Europe post-1991 was perceived within the Kremlin to be directed at Russia: a means of undermining a Russia that has, from Tsarist times, always feared a Western-inspired revolt that would unseat the incumbent regime.

And then there was the military threat. NATO expansion eastwards looked threatening to Russia, and a succession of Western- and NATO-led military interventions throughout the 1990s and into the 21st century seemed directed at traditional allies of Moscow. Would Russia be next on NATO’s list? Many in Moscow believed it would.

What of Ukraine? While the Putin regime was not overly concerned that NATO had ended up on Russia’s borders, any possibility of the accession of Ukraine was a different matter. For many Russians, symbolically and sentimentally, Ukraine is part of their country. The Russian state itself began, indeed, in Kiev/Kyiv. Thus, Ukraine cannot be allowed to join the very NATO that threatens Russia.

Putin had, though, felt confident that Moscow could maintain a degree of influence over Ukrainian political leanings if pro-Moscow leaders were in place in Kyiv. But once President Viktor Yanukovych was removed from power in the Maidan events of early 2014, the Pavlovian response of Moscow was to act. Crimea (with its over 100 Russian military bases) and parts of Donbas were then seized. A Ukraine thus dismembered and destabilised, with an ongoing conflict on its territory, was never going to be allowed to join NATO.

If President Putin’s war in Ukraine is successful, that sends a very dangerous message to the international community.

BEN WALLACE

And the West largely did not react in 2014. A few sanctions were imposed but Russian oil and gas kept flowing to Western markets and Russian oligarchs went about their business. The signalling from the West was that Russian military interventions carried little cost: oil and gas supplies mattered more than altering state borders, contravening international law and killing hundreds of people.

Then there was perhaps the ultimate trigger for the 2022 invasion. Putin had been facing growing unpopularity within his own country. He could be removed by the growing power of opposition figures. What he needed, as the populist leader he portrayed himself to be, was an act that would unite the people behind him. He could undertake what one Tsarist minister had once called a ‘short victorious war to stem the tide of revolution’. That comment referred to Russia going to war with Japan in 1904 in a welter of nationalistic, pro-Tsar sentiment that could keep him in power. But that war, of course, did not end well for Russia and the Tsar and it did little to stem the tide of revolution.

Russian tanks rolled into Ukraine in February 2022. But the miscalculations were many. Putin’s intelligence services had assured that Russian troops would be welcomed with open arms. The war would be a short and victorious one. They were wrong. The Russian military was also in no position to conduct the invasion. It was undermanned and ill-prepared. On the strategic plain, Putin and his coterie likewise misunderstood the degree of opposition his intervention would generate, especially within Europe. This time Putin has gone too far. The levers of oil and gas can only deliver so much in terms of diplomatic effect. Putin may yet, like the Tsar, come to regret his ‘short, victorious war’.

A collapsed bridge in downtown Bakhmut, Ukraine after it was torn down to halt the advance of Russian troops

Following the invasion, prominent academics from King’s School of Security Studies and King’s Russia Institute shared their expert analysis at a major conference on ‘The Defence of Europe’, with speakers including Ukraine’s Ambassador to the UK and the UK Defence Secretary, with an international audience of more than 400 guests in person and hundreds more online. The audience included diplomats, business leaders and policymakers, who were present to hear about the implications of the war for future European defence.

UK Secretary of State, Ben Wallace, said: ‘If President Putin’s war in Ukraine is successful, that sends a very dangerous message to the international community.’

He believes that Putin makes more strategic blunders than he makes strategic successes, but acknowledges that in order to win a war, it’s not always necessary to have the best kit, training or appropriate rule of law. You just need to be able to be more brutal than the other person.

He continued: ‘If you win your war by killing, murdering, raping, bombing civilian territories, breaching all human rights, all Geneva Conventions, corruption, and that becomes the battle-winning component, the message that sends to other adversaries around the world is incredibly dangerous.’

You can find out more about the conference here.

King’s world-leading prowess in security studies is well known, and our academics have been called upon to elucidate the complexities of the invasion, delivering intelligence to select committees and briefing government departments.

Professor John Gearson, Head of the School of Security Studies, said:

‘Experts from across the school have provided cutting-edge analysis to the media, parliamentary committees, and government departments and agencies since the war began. Our goal has been to provide a better understanding of the factors affecting the war.

‘This range of opinions on the crisis has left the overwhelming impression that this is a defining moment for the security of our continent and indeed the world.’

Our goal has been to provide a better understanding of the factors affecting the war.

PROFESSOR JOHN GEARSON

In September, Dr Marina Miron, Honorary Research Fellow in the Defence Studies Department’s Centre for Military Ethics, shared her analysis with DW News (start at 3:31) on the Ukrainian counteroffensive against the Russian military invasion.

How far European countries are willing to sacrifice the good of their own citizens to help Ukraine remains to be seen.

DR MARINA MIRON

Sir Lawrence Freedman, Emeritus Professor of War Studies, shared his insight with Channel 4 News, stating that neither side in the Russia-Ukraine conflict can sustain the war for years.

While King’s insight and analysis has been helping to inform policy on the war, philanthropy is also playing an important role in King’s ability to make a positive difference thanks to the generosity of alumni and donors. A generous £3m donation from XTX Markets’ Academic Sanctuaries Fund is enabling King’s to support students and academics impacted by the war through the launch of a new Sanctuary Hub.

The Sanctuary Hub is a unique distribution model that provides a range of studentships and fellowships for individuals impacted by the war, including students and academics from Ukraine, Russia and Belarus. Centred around the needs of displaced students and academics, the studentships and fellowships are being offered by a network of university partners. The hub will also provide an innovative space centred on collaboration, research and policy development, with the aim of supporting forcefully displaced students and academics from around the world. As part of their resettlement, the students and academics supported by King’s receive support to enable them to thrive within the university community.

The Ukraine war is complex and its impact is wide-reaching. Through King’s long history of generating new knowledge and understanding of issues related to war and conflict in the service of society, we are helping to decode the developments as they happen. While we are harnessing the depth and breadth of expertise across the SSPP to decipher the impact of the invasion, our partners stand beside us to support those affected by the war in practical and concrete ways. Thanks to the support of alumni, hardship funding is also being made available to support students significantly impacted by the invasion of Ukraine. The endpoint of this period in history is unknown, but our commitment to knowledge and support is unwavering.

You can read more from our experts on the war in Ukraine here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

The Department of War Studies at King’s College London was established 60 years ago. In honour of this, we examine...

A look into the latest developments on the Strand Campus.

I would like to have seen more on the role of Belarus – in terms of its strategic importance to Russia, Putin’s fears following the demonstrations against Lukashenko in 2021, its role during the invasion of Ukraine and potential Western activity to apply pressure on Putin via Belarus.