Autumn / Winter 2021

Service to Society: Living out King’s ethos of serving society

Living out King’s ethos of serving society: a roundup of Global Day of Service events.

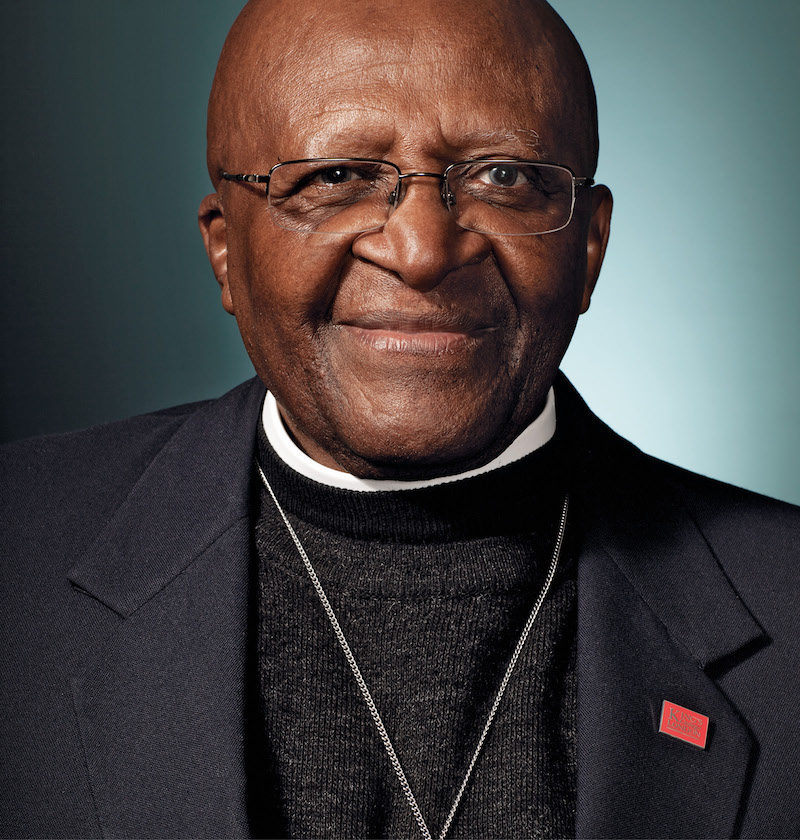

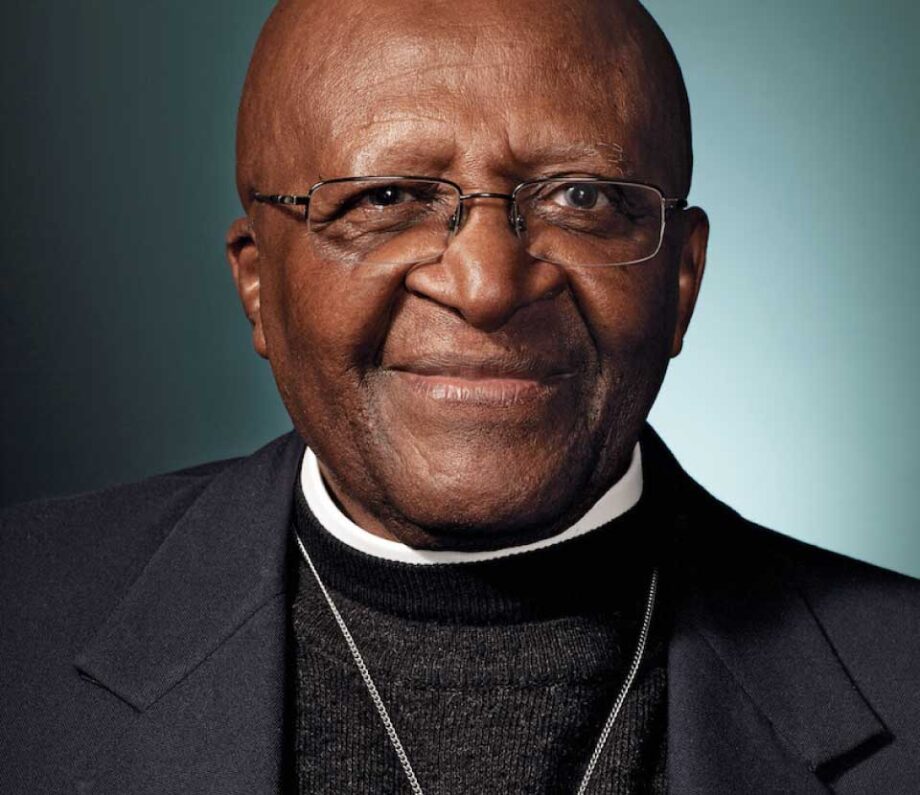

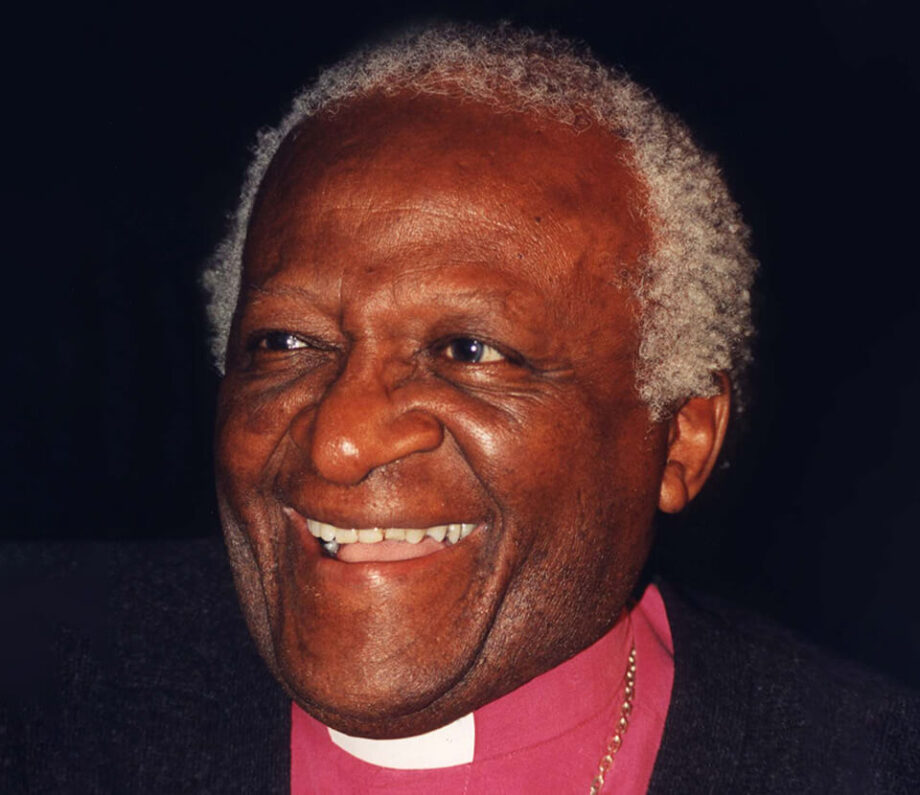

Archbishop Desmond Tutu

The journey of an icon -

1931 to 2021

Klerksdorp, South Africa, is the birthplace for the future leader.

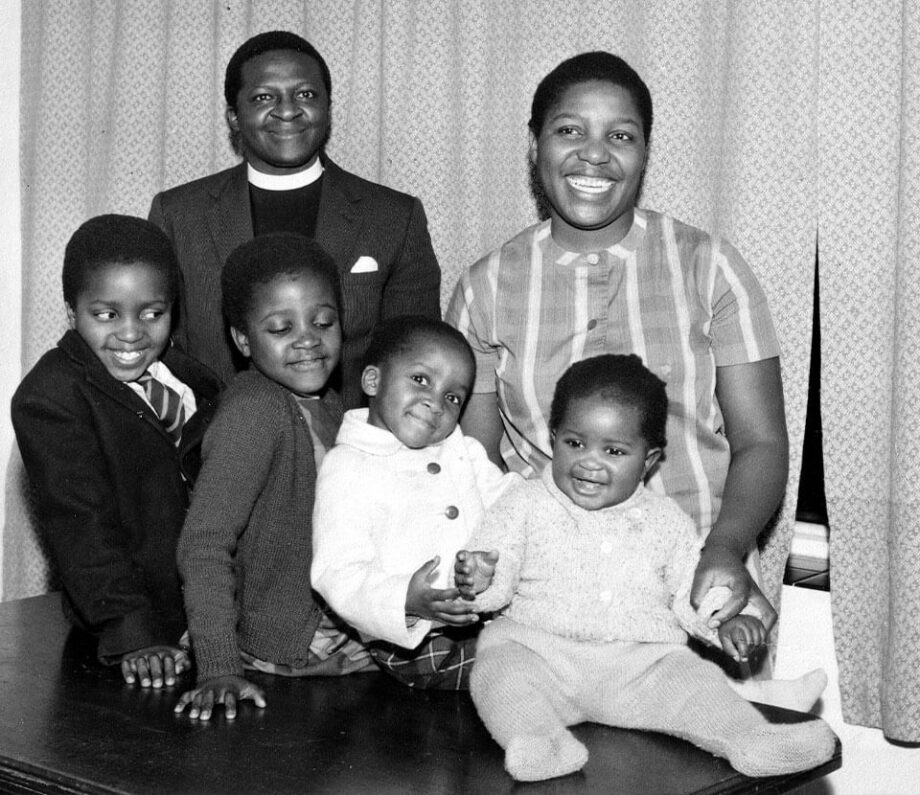

Archbishop Tutu’s family joins the Anglican church.

Marries Nomalizo Leah Shenxane and teaches at a high school, where his father is headmaster.

Moves with his family to England and graduates with bachelor’s and master’s degrees in Theology at King’s.

Returns to South Africa and makes his views on anti-apartheid known.

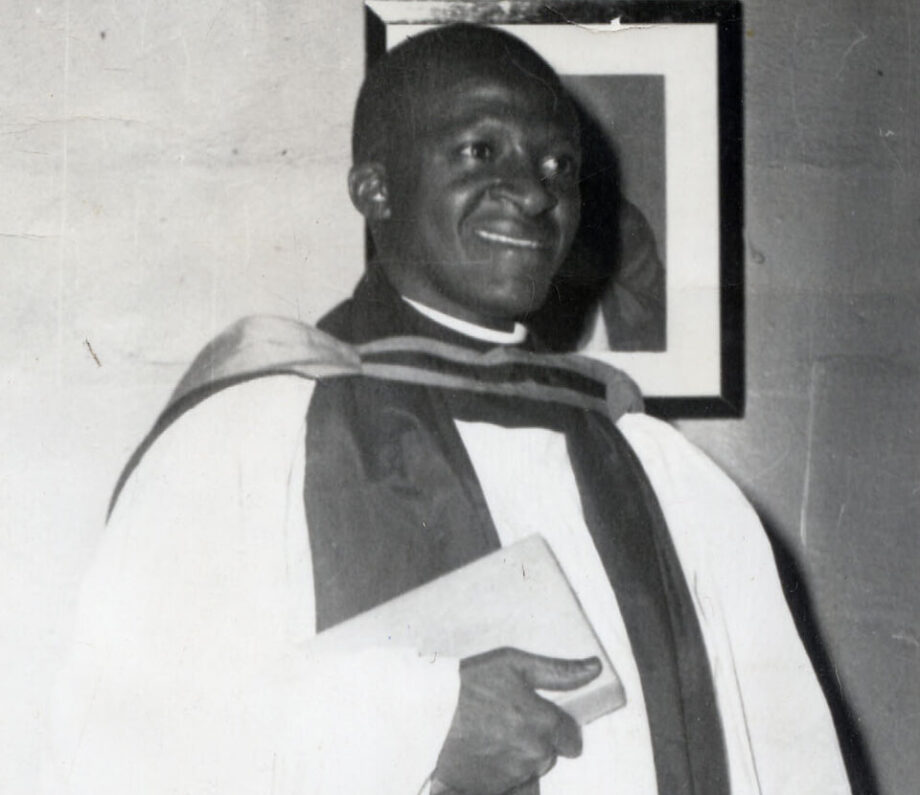

Becomes the first Black Anglican Dean of Johannesburg.

Is awarded the Nobel Peace Prize and becomes the first Black Anglican Bishop of Johannesburg.

Is appointed as the first Black Archbishop of Cape Town and Head of the Anglican Church, the role covering South Africa, Botswana, Namibia, Swaziland and Lesotho.

Is selected by President Nelson Mandela to chair the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

Retires as Archbishop of Cape Town and becomes Archbishop Emeritus.

Becomes Visiting Professor in Post-Conflict Studies at King’s.

King’s holds a grand celebration for Archbishop Tutu’s 80th birthday.

Passes away on December 26 at the age of 90, after a long battle with cancer.

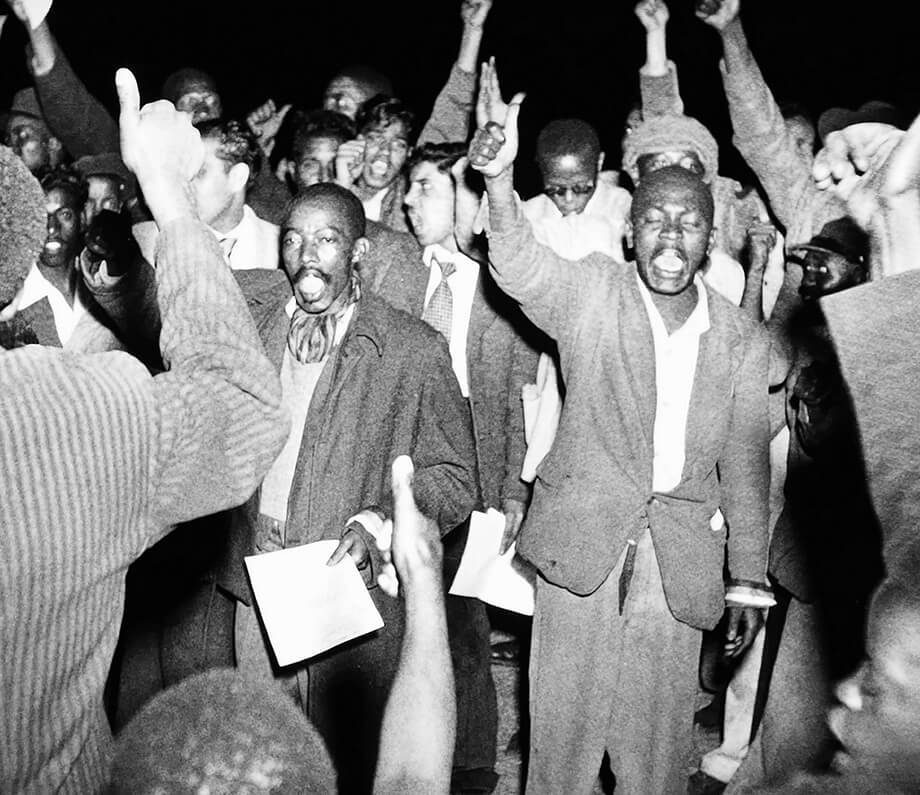

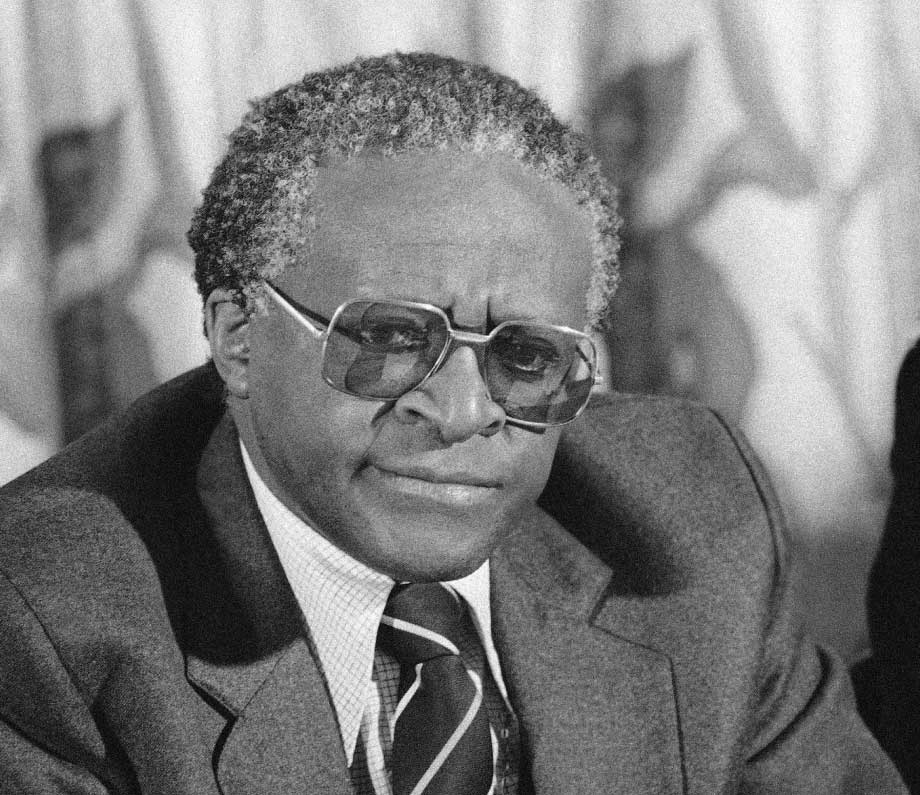

Arguably King’s most famous alumnus, Archbishop Desmond Tutu (Theology, 1965; MTh, 1966) was a trailblazer and a seminal voice in the anti-apartheid movement. Archbishop Tutu’s impact is profound and was made even more apparent when the announcement of his death reverberated worldwide, with King’s senior leaders and alumni communities providing touching tributes.

Here we celebrate Archbishop Tutu’s life, from his childhood in South Africa, to his leading role in the anti-apartheid movement and how he stayed close to King’s throughout his remarkable life. We also share tributes from King’s Dean, the Revd Dr Ellen Clark-King; King’s former President & Principal, Professor Sir Richard Hughes Trainor; and the Archbishop’s son, Trevor Tutu (PGCE Biology, 1978), as well as the many fellow alumni and friends on whom he made such an impact.

The future leader had humble beginnings in 1931, being born to Aletha Matlhare, a domestic worker, and Zacheriah Zililo Tutu, a teacher in Klerksdorp, in the North West Province of South Africa. Initially baptised as a Methodist, Archbishop Tutu’s family eventually joined the Anglican church. Archbishop Tutu aspired to be a doctor after overcoming tuberculosis as a child, but he became a teacher due to not having enough funds to pursue a career in medicine.

Archbishop Tutu married Nomalizo Leah Shenxane – a union that would last for more than 60 years – in 1955. In 1961, Archbishop Tutu became a priest; though he may have had a distinguished career as an Anglican priest in South Africa, his career progression was limited due to his lack of credentials. Further, his decision to leave teaching was partly influenced by South Africa’s lower education standards for Black children. Ultimately, Archbishop Tutu moved with his family to London to study at King’s. There, he was impressed by the fact that Hyde Park provided a forum for anyone to speak.

Archbishop Tutu thrived at King’s – an environment in which he could study the Old and New Testaments and listen to theologians’ recordings. After receiving his bachelor’s degree in Theology in 1965, Archbishop Tutu received his master’s degree in Theology from the Chancellor of the University of London, Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother, in 1966.

Archbishop Tutu said of his time at King’s: ‘I have wonderful, happy memories. My experience was one of great encouragement and support in my academic studies and an acceptance and warmth from my fellow students.’

Despite enjoying life in England, duty called, and Archbishop Tutu returned to South Africa as a lecturer and occupied various roles in the church. He eventually became the first Black General Secretary of the South African Council of Churches – this organisation became a force against apartheid.

1984 proved to be a celebratory year for Archbishop Tutu, who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize and became Johannesburg’s first Black Anglican Bishop. Archbishop Tutu emphasised non-violence, but he also shared: ‘I am a man of peace, but not a pacifist.’

The 90s saw the fruition of the efforts of the anti-apartheid movement, with Nelson Mandela being released from prison and becoming the first Black President of South Africa. At the time, Archbishop Tutu was selected to be Chairman of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. In this role, Archbishop Tutu collated testimonies of the atrocities of apartheid.

In his later years, Archbishop Tutu continued to be active – despite having various bouts of cancer since the late 90s. He returned to King’s as a visiting professor in 2004. As a writer, Archbishop Tutu published several books, including God Has a Dream: A Vision of Hope for Our Time.

Archbishop Tutu passed away in December 2021 after a lengthy battle with cancer. His frankness and bravery in the face of adversity and boldness leave a legacy that will impact generations to come. At the same time, he used playfulness and fun in the direst of circumstances. A light may have dimmed, but a fire has been ignited.

Credit: David Tett

King’s senior leaders and alumni communities provide touching tributes to Archbishop Desmond Tutu on his passing.

Here, the Revd Dr Ellen Clark-King, the Dean of King’s, shares her poignant experience as an attendee at Archbishop Tutu’s funeral in Cape Town (who she refers to as ‘the Arch’ in this tribute) and calls on the King’s community to uphold his legacy.

Surprisingly, my new year involved an unexpected trip to Cape Town on King’s behalf. It was an honour to be one of the 100 people attending Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s funeral, a privilege that had nothing to do with who I am, and everything to do with the place King’s had in the Arch’s life.

Three very moving conversations reinforced this. One was with his sister at a memorial event for friends and family. She told us that the Evensong from the Strand Chapel, which was livestreamed to their home on the Arch’s 90th birthday, was one of the last things he could enjoy before his final decline. Two Theology & Religious Studies students, one Christian and the other Muslim, moved Archbishop Tutu by saying how much his legacy meant to them today.

The second was with Mama Leah, as the Arch’s widow is affectionately known. She is not well herself but welcomed me to visit her at home, where I passed on letters of condolence from King’s Principal, Professor Shitij Kapur; Lord Geidt; and the bishops of London and Southwark. She smiled with great warmth to receive these tributes and told me how much it meant for her family for King’s to remember and pray for them.

The third was with his son, Trevor Tutu, in St George’s Cathedral just before the funeral. He sought me out to tell me how important King’s was in his father’s life. He repeated something that the Arch often said himself – that it was his time at King’s that had made him the man he was. Trevor reminded me that he was also a King’s graduate and pointed out that he was wearing his King’s tie to the funeral. I kept trying to tell him how honoured I was to be there, and he kept speaking over me to say how grateful the whole family was to King’s.

I wanted to share these stories to reinforce the deep and abiding impacts we can have on individual lives and, ultimately, the wider world. Archbishop Desmond Tutu was a remarkable force for good in South Africa and far beyond. And part of what enabled him to be that joyful, tireless worker for justice was what he learnt at King’s: the freedom to debate and disagree respectfully, how students worldwide could learn together and from one another, the joy of encountering new ideas and being challenged to be the best one could be.

It was a special honour to be present in Cape Town on King’s behalf. I hope that we can continue to be an institution with such a remarkable impact on our formidable students. May the Arch’s commitment to truth, reconciliation and justice continue to live among us all.

Revd Dr Ellen Clark-King, Dean of King’s

King’s senior leaders and alumni communities provide touching tributes to Archbishop Desmond Tutu on his passing.

The very close ties to King’s of that great alumnus, Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu, loomed appropriately large during the Principalship of Sir Richard Hughes Trainor (2004–14). Here, he shares his memories of ‘the Arch’.

Even before I took up my appointment at King’s, I met the ebullient Arch in early 2004 when he was in residence as Visiting Professor in Post-Conflict Studies. Then, soon after I became Principal, King’s began to organise the Cape Town celebration of the Archbishop’s 75th birthday. In his speech at that large and enthusiastic gathering in September 2006, in the splendid setting of the residence of the UK High Commissioner to South Africa, the Arch made clear – in his inimitable, irreverently witty fashion – the profound debt that this highly accomplished yet disarmingly humble Nobel laureate felt to his alma mater. For the Arch believed that King’s had taught him how to think systematically and had inspired in him the initiative necessary to speak out on crucial issues.

The Arch made many major visits to King’s during the next eight years. Among the events anchoring those visits were: an occasion for King’s staff in the Savoy Hotel (of all unlikely places!), the celebration at the Strand Campus of the Archbishop’s 80th birthday, he and his wife Mama Leah’s reminiscences (during the re-purposing of Tutu’s nightclub in KCLSU’s Macadam Building) of their time at King’s five decades before, the May 2013 award ceremony in the Guildhall for the Templeton Prize (which included glowing references by the Arch to his alma mater), a visit of ‘The Elders’ (of whom the Arch was of course one) to the Barbican Centre, and the Archbishop’s stirring eulogy for Nelson Mandela during the Westminster Abbey memorial service for the latter in March 2014. King’s was a place that the Arch manifestly liked to be, and every one of his visits was both busy and inspirational. He made everyone that he met at King’s feel very special.

Hosting the Arch on these various occasions was a joyfully intense process involving my close colleague Julie Thomas (now Director of Protocol in the Principal’s & President’s Office at King’s), my spouse Marguerite Dupree, the Development team (then led by Gemma Peters) and, above all, the then Dean of King’s, Richard Burridge, who looked after the spiritual as well as the practical routines of our eminent guest. For all of us it was an immense privilege, and a huge pleasure, to associate regularly with one of the world’s truly great individuals, who was perhaps the most enthusiastic and influential alumnus ever of King’s College London.

Sir Richard Trainor with Archbishop Desmond Tutu

King’s senior leaders and alumni communities provide touching tributes to Archbishop Desmond Tutu on his passing.

Here, Trevor Tutu, Archbishop Tutu’s son, shares how King’s gave his father a new perspective, his proudest moment, and what his alma mater meant to him.

My father was always really proud of having attended King’s and would insist that he went to the real King’s College, and that any others were nothing but crude imposters attempting to usurp the dignity and reputation of the far more august institution that he had attended.

In 1978, when I was doing my PGCE at King’s, my father came to visit from South Africa. He would have been in the transition between being Dean of Johannesburg and Bishop of Lesotho, and would certainly have had little or no international reputation. He had a meeting with the Dean and took me to lunch immediately thereafter. At lunch, he announced to me that he had been invited to become a Fellow of King’s. I would suggest that this was one of his proudest and happiest moments. I have not seen a dog with two tails, but he acted as though he was trying to show me, the waiter and the restaurant’s other patrons exactly how a dog with three tails might be expected to behave. The Nobel Peace Prize, the doctorates, the accolades… none meant anything to him. The fact that he could put FKC after his name was the ultimate honour. I can remember him saying that he did not have anything else to achieve now that he was a Fellow at King’s.

My father really came into his own at King’s and was able to cast off all of the doubts and feelings of inferiority that apartheid South Africa had attempted to engender. Even when you know that apartheid is a lie and blasphemous, there is a long dark teatime of the soul when a small nagging voice will whisper in your ear, ‘Verwoerd¹ might be right, you know.’ King’s allowed my father both the intellectual growth and the everyday human contact that proved in every waking minute that the nagging voice was lying.

I was only six when my father started at King’s, but I could see in the parties that we held at home that he was popular with his fellow students, and that he was enjoying his time there. He used to regale my mother and us children with the stories of what went on in college. I am sure that King’s meant friendship, and fun and laughter; but it was also a time of remarkable intellectual and personal growth.

Having become a Fellow, my father was always informed of matters at the university, and of course was invited to the Fellows’ dinners. He also had a sabbatical where he was a visiting professor in both peace studies and theology.

Most famously, my father opened the Students’ Union bar, and it was called Tutu’s, but that was after me and not him, as I would have had more use for it. But it’s a common mistake that many people make.

My father was also a great friend to a number of the Deans at King’s – Sydney Evans, who made him a Fellow, and Richard Burridge, who often came to visit us in South Africa – so the ties went very deep.

¹ Hendrik Verwoerd, the South African politician commonly regarded as the architect of apartheid.

Trevor Tutu with the representative of the Dalai Lama, Ngodup Dorjee Credit: Central Tibetan Administration

King’s senior leaders and alumni communities provide touching tributes to Archbishop Desmond Tutu on his passing.

I met Archbishop Tutu in 1962 as we both embarked on a divinity degree as mature students at King’s. We were both married with families and were the only South Africans on the course. We were delighted to meet each other because neither of us knew much about England, so we spent three years at King’s side by side, becoming close friends and exploring London. We were shocked the first time we went to Speakers’ Corner in Hyde Park and heard people voicing their disapproval of the government aloud and in public. Based on our experiences in South Africa, we looked nervously around, expecting security to arrive, and almost ran away. Archbishop Tutu’s wife Leah used to ask police employees the time to delight in their polite response.

As well as new experiences there was much laughter, and I got used to Archbishop Tutu’s famous loud chortle. I stayed in the UK and he returned to South Africa to continue his church work. We didn’t meet again until 1986 when he came to Wales. It was a joy to see him, but I remember feeling guilty and wretched when he said he needed me in South Africa to help the cause of freedom and that things there were tough. I stayed in the UK mainly because two of my children were in their exam years. That said, the 80s for Archbishop Tutu were difficult and dangerous, and I felt very torn.

We met several times in South Africa after the end of apartheid, the first being when he was struggling with the traumas exposed by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Archbishop Tutu was exhausted by all that he heard. He was a man of profound faith in action: fighting for social justice, human rights, diversity and equality. He fearlessly challenged the wrongs in South Africa and in the wider world, championing the rights of the poor and marginalised. I remember him saying once: ‘If there are no gays in heaven, I don’t think I want to go there.’ He abhorred exclusion and exploitation. His moral reach was global. It began with peace and forgiveness in South Africa but extended to warnings of the climate emergency.

In 2004, he said: ‘Ecological concerns are a deeply religious, spiritual matter.’ He refuted criticisms of interfering in politics. He asserted that those who claimed the church should confine itself to theology and not meddle in politics were reading a different Bible from his.

Archbishop Tutu’s belief in the African philosophical idea of ‘Ubuntu’ – we are all linked through our common humanity – was deeply held and was evident in his behaviour. He believed in the value of every single human being on the planet and that we must all care for one another.

We lost a global icon on 26 December 2021, and we all mourn his passing. I feel privileged to have known him and become his friend, as many others did. He will not be forgotten, and neither will his laughter. My wife Carole’s favourite memory of him was when we were at a reunion meal at King’s and she was sitting next to him. She realised she’d dropped an earring somehow and the next thing she knew was that he’d dived under the table to retrieve it, emerging triumphant. When the waitress reappeared, he ordered rum and raisin ice cream, which wasn’t on the menu, but she somehow conjured it up. After all, it was his favourite dessert. Hamba kahle, Archbishop. Go well. Rest in peace and rise in glory.

King’s senior leaders and alumni communities provide touching tributes to Archbishop Desmond Tutu on his passing.

I remember Archbishop Tutu well; we studied together between 1962 and 1964. He was the only Black theological student. His laugh then was as remarkable as it was over the last years of his life. He was intense in his academic life: a serious and lovable student.

Little did I or anyone know what was ahead after his life at King’s. Although I did not know him personally, I consider it a wonderful privilege to say I studied with him. Upon reflection, it is easy to say how the theological faculty at King’s played a great part in his spiritual and political life. Sancte et Sapienter.

King’s senior leaders and alumni communities provide touching tributes to Archbishop Desmond Tutu on his passing.

In 2004, Archbishop Desmond Tutu returned to King’s as Visiting Professor in Post-Conflict Studies. Towards the end of his tenure, alumni were invited to a service in the Chapel at which he gave the address. His speech was bubbly, full of humour, but also shocking. One thing that has remained with me was his description of his earlier time at King’s. At his first lecture he found himself sitting next to a white person – something he had never done before. He also spoke of the tremendous, new experience of freedom:

‘It was, for me a breath of fresh air – really, gale force winds – to have been taught how, and not what, to think, as had happened in the claustrophobia of South Africa; which was seeking to produce obsequious and uncritical creatures… Here [I was] able to live anywhere! – walk about freely, without needing the justification to be there by the iniquitous Pass Law system that restricted the movement of Blacks so severely in the land of South Africa.’

When the service was over, he stayed – full of bounce and liveliness – to chat to people and to greet joyfully those he knew well. It had been a tremendous evening, and later I wrote to thank him.

On Saturday mornings, my husband Tim and I used to have breakfast in the dining-room – complete with a snowy-white cloth on the table and a large teapot. One Saturday, we were still at the table when the post arrived. I opened an envelope addressed to me and was startled to discover a handwritten letter from Archbishop Tutu, thanking me for my letter to him. Tim was so astonished at his response that he absent-mindedly picked up the milk and was about to pour some into the teapot instead of his cup. Luckily, he caught himself just in time, but he blamed Archbishop Tutu for this near-catastrophe and declared that if he had poured milk into the pot, then the archbishop’s name would have been to blame.

Shortly after, I wrote to Archbishop Tutu again, to thank him for his letter, and I told him about the milk incident. A day or two later, I received another note; my letter had arrived on Archbishop Tutu’s last day at King’s, and he had not had time to reply to me personally but had asked someone to do so on his behalf. And his closing message: ‘I hope that no-one pours milk into the teapot!’

King’s senior leaders and alumni communities provide touching tributes to Archbishop Desmond Tutu on his passing.

I can’t remember the date, but I came a few years ago to hear Archbishop Tutu preach at a service in the chapel. I was amazed that I sat within a few feet of him with no additional security.

My outstanding memory of his sermon was when he mentioned his time in London as a student – he couldn’t believe police were there to help you, unlike his home country. He told us of his joy of going up to a police officer to ask the time and being told it. He giggled at the memory of it; it was wonderful. The world is a sadder place without him.

King’s senior leaders and alumni communities provide touching tributes to Archbishop Desmond Tutu on his passing.

Archbishop Tutu and I were contemporaries at King’s between 1962 and 1965 to receive bachelor’s and master’s degrees in Theology. We knew he was special then, but how could we know that he was going to be so influential in bringing apartheid to an end!

We were in the same, small seminar group for one of our optional specialist subjects, and we were fortunate to have Professor of New Testament Studies, Christopher Evans, as our tutor. These seminar groups were timed for one hour, but they often went on for nearly three hours! They were among the highlights of my time at King’s.

I was fortunate to be on a pilgrimage with Tutu and Leah when he was Archbishop of Cape Town. For 16 days we travelled through Turkey and Greece to places at which Paul the Apostle had preached. There was much laughter and many tears as we realised he was going back to South Africa during those critical years between 1988 and 1990.

We remained in touch, exchanging Christmas and birthday cards, and sometimes flowers. I often met him when he was in London, Birmingham and St Albans, when he was in the UK for preaching engagements. I arranged reunions of our Theology class of 1965 at King’s, and he and Leah attended these large gatherings. I was also invited to attend Archbishop Tutu and Leah’s 50th wedding anniversary in Soweto in 2005. This was a wonderful occasion at a more relaxed time.

So many memories of this man, who had a big heart and who became a giant spokesman for justice, racial equality and human rights.

King’s senior leaders and alumni communities provide touching tributes to Archbishop Desmond Tutu on his passing.

It is a source of pride to me to attend the same university as Archbishop Desmond Tutu. As a Christian, I appreciated his commitment to God and how the love of God and His principles formed the bedrock of Archbishop Tutu’s activism. He was able to work with people of all backgrounds for good. Bless Archbishop Tutu’s memory, and may we commit to standing for the right, justice and the practice of godly love to all who need it. It is evident to all that politics alone does not have the answers to humanity’s problems.

King’s senior leaders and alumni communities provide touching tributes to Archbishop Desmond Tutu on his passing.

We first met when studying Theology in 1962. Greek classes taught by the Revd Gordon Huelin were often accompanied by teasing, with Archbishop Tutu happily accepting jokes against himself.

Some years later, Archbishop Tutu heard I was in hospital with an eye problem. He telephoned the ward and the sister called me to her office. He wished me well and told me to tell the doctors and nurses that he was praying for them. After the call, the sister came to my bed in some puzzlement: ‘I’ve never had a Nobel Peace Prize winner call my ward before.’ This kindness was just typical of Archbishop Tutu.

At the service marking my retirement from full-time ministry, a church warden read out an email. It was, of course, from the Arch: ‘What’s a spring chicken like you doing retiring so young?’ he wrote in jest.

However, this prompted me to write suggesting that my wife and I might meet with him in Cape Town during our trip to South Africa. Archbishop Tutu replied with an invitation to lunch, during which, looking out over the bay towards Table Mountain, he remarked: ‘Didn’t God do a splendid day’s work making that?’

During our days at King’s, I remember the Professor of Old Testament Studies, Peter Ackroyd, sometimes using the phrase, ‘It is not unreasonable to suppose that…’ I remember Archbishop Tutu being astounded at that open-minded approach to academic study – something he had not been able to experience during his earlier theological lessons in the rigid and uncritical atmosphere of his native, apartheid-dominated South Africa.

The light which Archbishop Tutu shone throughout his ministry must never be extinguished. As he once said – and this is of great significance in our present political climate: ‘If we can get rid of apartheid, there is no reason humankind cannot get rid of nuclear weapons.’

King’s senior leaders and alumni communities provide touching tributes to Archbishop Desmond Tutu on his passing.

I live in New York City, but for the past 30 years, my wife, Kathy, and I have spent summers at our house on Shelter Island, which is an idyllic retreat off the eastern end of Long Island, New York. Through our church out there, we became friendly with Lynn Franklin, who was Archbishop Tutu’s literary agent.

Archbishop Tutu would often visit Lynn; he enjoyed the privacy and relaxation which this small island provided, and so was never highly visible while staying there. However, one summer about 20 years ago, Lynn invited a small group of perhaps a dozen of her friends to her house for brunch, and to celebrate Eucharist with the great man.

I was quite nervous about meeting this very famous individual: I even researched the appropriate way of addressing an archbishop (‘your Grace’). However, with Tutu there was no need for formalities; he was the jolliest of men and was happy to be called simply ‘Tutu’.

I graduated from King’s College in 1964, and when I informed him that he and I attended King’s at the same time, he was simply gleeful. He reminisced about his time there; we discussed the fun that the college mascot, Reggie the lion, provided, including when this statue was ‘kidnapped’ by our rivals at University College. I believe we even started singing what we could remember of the College song.

Although I never directly interacted with him while at King’s, I do have this vague memory of this very distinctive African man in a clerical collar roaming the halls. To spend time in his company almost 40 years later was an honour I shall never forget.

King’s senior leaders and alumni communities provide touching tributes to Archbishop Desmond Tutu on his passing.

I was privileged to be in my final year at King’s when we celebrated our 175th anniversary. I was thrilled that Archbishop Desmond Tutu FKC would be a visiting professor during this time. He clearly loved King’s and the time he had spent as a student. His reminiscences were wonderful. We were riveted by his words, being challenged to approach others with compassion and love. Whether that person is a victim of injustice, a perpetrator of atrocities, an infamous politician or a homeless person, Archbishop Tutu emphasised the importance of seeing their humanity and the image of God in them.

Archbishop Tutu’s experiences in South Africa showed how to end the cycle of violence and hatred, but it could not be a one-off process: we must continue to seek out the human and the divine in people. We need this message more than ever. Eternal memory!

King’s senior leaders and alumni communities provide touching tributes to Archbishop Desmond Tutu on his passing.

At the 40th Anniversary of Holy Trinity Church, I had invited Archbishop Tutu to open a migrant workers’ help centre in Dubai. His secretary was doubtful: ‘The Archbishop is over 80 and has cancer. No he wouldn’t want to travel, preach… nor celebrate!’ Knowing Archbishop Tutu, I asked again: ‘How many steps would he need to climb to the help centre?’ she asked. My secretary checked and returned with a smile: ‘He is coming!’

‘How do you know?’ I asked, surprised by her sudden certainty.

‘There are 22 steps!’

Archbishop Tutu celebrated, preached, climbed the steps and showered the huge crowds below with Holy Water as they sang the hymn, ‘There shall be showers of blessings’!

A wonderful memory.

King’s senior leaders and alumni communities provide touching tributes to Archbishop Desmond Tutu on his passing.

I was in the UK in 2010, having been awarded a Commonwealth Professional Fellowship at the Law Society of England and Wales. I had been in Cape Town in 2009 to participate in a human rights colloquium to speak about the experience in South East Asia. I wrote to ask whether I could call on Archbishop Tutu, but was told he had been unwell and was not receiving visitors. When I heard he was in London in 2010, I wrote again, and this time was invited to meet with him. We had met briefly twice before when I was a student at King’s, but it was good to sit down and speak with him about the human rights situation with respect to freedom of religion or belief in Malaysia. It is a moment I will always remember fondly.

Andrew Khoo AKC with Archbishop Desmond Tutu.

King’s senior leaders and alumni communities provide touching tributes to Archbishop Desmond Tutu on his passing.

I met Archbishop Tutu completely by surprise when I called into the working men’s club where we lived and he shook my hand, such a warm hand, and made me feel so proud that he was one of us.

King’s senior leaders and alumni communities provide touching tributes to Archbishop Desmond Tutu on his passing.

I remember Archbishop Tutu vividly. He was not then the icon that he later became, but he was universally liked by all those who knew him at King’s at that time. One remembers that infectious smile and that he always seemed to be looking upwards.

King’s senior leaders and alumni communities provide touching tributes to Archbishop Desmond Tutu on his passing.

King’s was my first-choice university for my French with English degree, and I remember the moment that I knew it would be an incomparable home for my scholarly endeavours. Having wandered the halls as a Fresher, I was told that the bar and events space had been named after that shining light: the man who, alongside Nelson Mandela, helped to end apartheid, Archbishop Desmond Tutu. That great man, a Black man, had walked the same halls years before and gone on to change history. I lit up at that moment myself. It meant the world.

King’s senior leaders and alumni communities provide touching tributes to Archbishop Desmond Tutu on his passing.

Little did I know, when I studied in the theological library at King’s with Archbishop Tutu, where his studying would lead him. I especially want to thank him for:

his trust and steadfastness in taking seriously Jesus’s challenge to love our neighbours and enemies,

his courage in standing up to evil,

his skill in challenging the opposition,

his willingness to suffer for his beliefs,

his understanding of the needs of humanity,

his teaching on and example of what it means to be human,

his communications talents through word, smile and dance.

May we, too, seek to follow in his footsteps!

Thank you Arch. You did King’s proud.

King’s senior leaders and alumni communities provide touching tributes to Archbishop Desmond Tutu on his passing.

A short poem for Archbishop Tutu

A great man

Always smiling

You will be forever missed

All alumni who met you at the Strand that cool, inspiring evening will miss you.

Rest in peace

King’s senior leaders and alumni communities provide touching tributes to Archbishop Desmond Tutu on his passing.

I had the honour of meeting Archbishop Tutu while I was at a restaurant in Cape Town in January 2020; he was dining at the same restaurant. I am also a King’s Theology graduate (1988) and I wanted to ask him about his time at King’s and if he did the AKC (Associateship of King’s College). He said he loved his time at King’s and didn’t do the AKC. It was so lovely to chat to him.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Living out King’s ethos of serving society: a roundup of Global Day of Service events.

Adewale Akinnuoye-Agbaje (LLM, 1992) is a British actor, writer, director and musician. He is best known for his roles in...

This year, the events surrounding the deaths of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd, and the shooting of Jacob Blake and...

Those who have been fortunate to meet Desmond Tutu will know just how effervescent he is. I was a fresher when I first encountered him, then a mature student, at King’s College London. He was also serving as a curate in the North London church where I had been a chorister. It was obvious that the academic staff at King’s (at that time largely Anglican) admired him hugely. I met him again in the early 1980s when staying at the South African Council of Churches in Johannesburg, where he was General Secretary and – as we know from John Allen’s widely acclaimed Rabble-rouser for Peace: The Authorized Biography of Desmond Tutu (Rider Books, 2006) – in serious danger of assassination. A decade later I stayed with him, by now Archbishop and Nobel Peace laureate, at Bishopscourt in Cape Town. It was difficult not to be in awe of his sheer courage and moral passion – challenging the murderous apartheid regime and speaking the truth, then and later, to those in power.

Throughout my training (AKC 1969) and ministry Archbishop Tutu has been a continuing inspiration, especially in his own ministry and writings. Thinking of him, one word comes to mind: JOY!

Well I didn’t meet the Arch at King’s – where I graduated in Philosophy- I didn’t even know he had been to King’s but I met him by accident when I just happened to walk across the recreation ground and -for some reason- stopped by the local working men’s club and there was Archbishop Tutu! He shook my hand and I felt so honored and surprised and ‘gobsmacked’! People didn’t believe me.

What an honor to be greeted by Archbishop Tutu!

May your service to Buddhist Dharma and war against apartheid remain vivid in the minds of all , may there be peace and equality in the world. Rest in peace TuTu!

A happy and devoted servant who inspired us all on the hopeful road.

Desmond Tutu and I started our life at King’s in the same term, Autumn 1962. As fellow “new boys” we always greeted each other in the corridors for the next three years. His smile was always present and lit up, what I thought, were the dreary corridor surroundings! I graduated as a chemist, but eventually was ordained and came across Desmond several times in my new life. He was always an inspiration to my ministry.

In October 1962 a group of men and women began a B.D degree or A.K.C course in theology at King’s College London. I was one of them, Father Desmond Tutu was another. What stood out about him then and has remained all through his life was the sheer joy of God that shone from him, and his mischievous sense of humour. He was a humble man, that is to say he recognised his gifts and was prepared to use them wherever appropriate. For him that meant upholding the dignity of all human beings, seeking justice wherever there was injustice, often at great personal risk, because ‘all people matter and matter enormously, because they are created in the image of God.’

A remarkable man with humanity at heart. Admired for bringing liberty to South Africa from the evil apartheid along with Nelson Mandela.